General Election: June 28, 2021 Candidates for Tribal Council

RICKY COMPO

TAMARA KIOGIMA

LEROY SHOMIN

DOUG EMERY

WILLIAM ORTIZ

MARCI REYES

KENNETH DEWEY

AARON OTTO

SHARON SIERZPUTOWSKI

SIERRA BODA (WITHDREW 5-14-21)

This logo uses ancient LTBB values with representation of two respective spirits of water and air. The two Water Panthers on the left, which are water spirits/deities, are of female and male origin. The Thunderbird on the right, an air spirit/deity, is usually thought of as of male origin. These spirits often battle, but also represent balance, which is why they are depicted in the same plane in our logo. The border around the spirits is of Odawa origin and is reminiscent of otter’s tracks with the dots being paw prints and the dashes being a dragging tail or slide.

Some translations of places are literal translations of contemporary/English names, although some of the English names come from the Anishinaabe name, such as Bear River. Other names are intact and were used prior to European contact.

The Odawa are a people whom have a deep connection with their environment. Whether it is the trees, plants, sky, earth or any living species, the Odawa interacted in a harmonious balance with their relations. But one element stands out in this relationship between a people and their home and that is the relationship to water. Being from the Great Lakes, the largest body of fresh water on the planet, water plays a vital role in the history, culture, beliefs, economy and even the political background of the tribe, to this very day.

The Odawa have historically lived in the middle of the Great Lakes, with villages in Ontario at Georgian Bay, Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula. Odawa villages extend west to Mackinac and the islands of Beaver, High and Garden in northern Lake Michigan. Follow the eastern coastline of Lake Michigan and Odawa villages extend all the way down to the Grand River. Odawa villages were also on the northern shore Lake Michigan, along the southern edge of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, stretching from St. Ignace west to Manistique. Predominately the Odawa established their villages along the shores of the Great Lakes. Odawa communities at these locations are still in existence to this very day, with reservations and large populations living there. The placement of villages along the water speaks to the importance of the water itself.

The word Odawa translates into “trade” in Anishinaabamowin, the native language of the Odawa. This term aptly applies to the Odawa as a people, as they were expert traders along the many rivers that supply the Great Lakes, as well as the big lakes themselves. The Odawa had established pre-contact trading patterns in the Great Lakes. Taking corn and tobacco grown in the southern portion of Michigan and Ontario from the Huron, they would trade these commodities with northern tribes, such as the Ojibway and Cree, near Lake Superior and beyond. Here, the Odawa would trade for meat, hides and other goods from these northern tribes. Acting as middlemen, the Odawa carried out an important trade of food, supplies and other goods for many tribes. The Odawa also grew large amounts of corn, which they traded themselves, as well as produced maple sugar and woven mats for trade. Like any organized society, trade was an important diplomatic element, which ensured peace, prosperity and access to natural resources. The vehicle for trade was the canoe.

Perhaps no other people in the Great Lakes were as skilled at navigating the treacherous waters of the Great Lakes as the Odawa. With their canoes, which were constructed of birchbark, cedar frames and held together with spruce root and pine pitch, the Odawa would haul up to four tons of goods. The Odawa would spend months on the water carrying out their trade. This travel also extended to rivers, some of which were very dangerous, such as the French and Ottawa rivers. No other tribe is recorded as going out of the sight of land in their maritime voyages, except the Odawa.

Upon first contact with Europeans in the 17th century, the Odawa were automatically seen as valuable partners, because of their existing trade networks and knowledge of the lakes. This economic relationship would help define military alliances during the Iroquois War, French and Indian War and War of 1812. The French partnered with the Odawa on building a strong relationship based on trade. Without the knowledge of the water, the Odawa would have been at a disadvantage in their positioning among Great Lakes tribes.

Odawa trade excursions would extend hundreds of miles. The hub of trade was the straits of Mackinac, which is the aboriginal lands of the Odawa and Ojibway of the upper Great Lakes (other bands of Odawa and Ojibway from southern Michigan and northern Ohio are different political entities, that don’t have strong claims to Mackinac). Starting from Mackinac, Odawa traders would paddle to Montreal, a 1,200 mile roundtrip journey. Other destinations were Detroit, Green Bay and Lake Nipigon. As natural resources became scarce, trade extended to Lake Winnipeg. All of this trade was carried out in birch bark canoes, using the Great Lakes as the major transportation routes of the day.

Wars were waged over trade resources and trade routes, especially the Iroquois War and French and Indian War. The Odawa fought to retain their position in the fur trade, their rights to areas to trade, trade relationships and the routes themselves. The Ottawa River in Ontario was originally named the Algonquin River. But due to the heavy traffic of Odawa traders on that river, the name of the river changed to “Ottawa”, even though no major Odawa villages were along this river. In addition, the Odawa would “tax” other native trading parties to use the river, as they had the right to do so. The water served as a powerful economic element for the Odawa.

The trade the Odawa engaged in brought new technology to western tribes, such as the Cree, Lakota and western Ojibway. The guns, knives and metal goods of European manufacturing altered every native nation they came in contact with. Click here for a map of the trade routes the Odawa used in the historic time period.

The belief and practices of caretaking for the dead has been a cornerstone of Odawa traditions for many generations. Annual “ghost suppers” or “feasts of the dead” have been occurring in Odawa communities for hundreds of years to the present day. These ceremonial feasts are held to feed the ancestors whom have passed on and maintain a relationship with them. Traditionally, Odawa villages would be located very near to burial grounds, where the families would hold their annual feasts of the dead, as well as keep the burial grounds well taken care of. The location of burials is a very important factor as well.

The vast majority of Odawa burials are located in very close proximity to water. Whether it be on the shoreline, near a river or on an island, the dead are near water. Major historic Odawa villages, such as Cross Village, Middle Village (Good Hart), Seven Mile Point, Harbor Springs, Bear River (Petoskey) and Pine River (Charlevoix) all have burials on their shores. Many of these burials are modern day cemeteries. Mackinac City is another Odawa village that has numerous burials along the water. Through work under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), LTBB has seen exactly where many burials were located in Emmet County. Working to get the ancestral remains returned from museums under NAGRPA, this information is obtained by LTBB. Through these records, 90% of repatriated remains in Emmet County are from the shoreline. Another major burial location is the islands the Odawa have called home, such as the Beaver Islands, Bois Blanc and Mackinac Island. Thousands of Odawa have been laid to rest along the waters edge in the upper Great Lakes, at Mackinac, the islands and Waganakising.

The Odawa fought hard to stay in their native homelands during the 1830s and 40s, when removal of tribes to western territories was occurring. One of the reasons the Odawa felt so strongly about staying home was to carry on their traditions of being near their dead and caretaking for them. Multiple letters, petitions, etc. were written to the United States during this time period, specifically stating the Odawa need to be near their ancestors.

The Odawa have long been expert fishermen on the Great Lakes. Not only did their skill using canoes serve them well in trade and travel but in fishing as well. The Odawa used nets, as well as spearing and hook and line, to catch fish. Fish was their most stable source of protein and along with corn, constituted the majority of their diet. Fishing with nets provided an individual with the greatest opportunity to not only feed his immediate family but his village as well. The use of nets goes back thousands of years for the Odawa.

Many villages’ sites that have had archeological work performed on them show an abundance of fish bones, verifying the importance as a food source. Sturgeon, whitefish and trout were the main fish caught, but many others supplemented the diet. Fish could be dried for later use or traded. Also, being in and on the lakes all the time, the Odawa knew that if they had the skill to fish, they would not starve. This was another powerful motivation for the Odawa to avoid removal during the 1830s. If removed to Kansas or Oklahoma, the entirely different landscape would not be conducive to their survival.

In the 1970s and 80s, Indians fishing with gill nets was a highly controversial activity in the Great Lakes. Ojibway and Odawa fishermen from Wisconsin and Michigan were being challenged by the State of Michigan and non-native sports fishermen on the right to use gill nets. The tension became so great that acts of violence were committed against native fishermen. Boats, fishing equipment and trucks were vandalized and destroyed. Fishermen were harassed and at times, assaulted. Anishnaabek fishermen put themselves in harm’s way on many occasions to exercise their rights to fish on the waters of the Great Lakes. These rights, which are inherent in the Anishnaabek, having utilized the Great Lakes for subsistence for thousands of years, are also treaty rights, which the Odawa and Ojibway reserved for themselves during treaty negotiations during the 1836 treaty of Washington D.C. It was under treaty rights that the Odawa and Ojibway of the 20th century were claiming the legal right to fish with nets.

The fishing issue brought to the public and legal forefront treaty rights overall for the Odawa and Ojibway. Claiming the rights to fish under treaty, the Odawa and Ojibway would not back down from an array of opposition. With multiple Anishnaabek fishermen getting arrested and appealing their cases, the fishing argument made its way to federal court. After several years of trial, the landmark court case of U.S. v Michigan was decided upon by Judge Fox, in which he ruled that the Odawa and Ojibway of Michigan, under the 1836 treaty, do indeed have a right to fish the Great Lakes with nets. The State of Michigan appealed the decision but the Supreme Court would not hear it.

Fishermen from Bay Mills were the more well-known during this time period, due to Bay Mills being a federally recognized Indian tribe. But LTBB fishermen were also exerting their treaty rights to fish, despite LTBB not having federal recognition. The Northern Michigan Ottawa Association (NMOA), which was the political body of the Odawa during the 1940s-80s, had been issuing its own fishing licenses to its members in the 1970s. The Odawa knew their rights under treaty. Organizing to argue their right to fish was one way the Odawa exercised their own form of government. This was critical during the 1980s for LTBB Odawa.

In the 1980s, the Odawa of northern Michigan were pushing for their status as a federally recognized Indian tribe in the United States to be reaffirmed by the United States. This path of reaffirmation was never taken before. Odawa fishermen, such as John Case from Charlevoix, were an integral part of the tribe’s effort during the 1980s and early 1990s. With Odawa fishermen on the Great Lakes fishing, this action essentially claimed the Odawa had treaty rights. During the 1980s, the LTBB community was holding large elder and treaty councils at Wycamp Lake in Cross Village. During these councils, hundreds of Anishnaabek from the Great Lakes would gather to share information, stories and strategize on the next steps of achieving federal status. The lake itself was important in these gatherings, as it was traditionally an area where Odawa would meet. The Odawa name for this lake is Spirit Lake. Spirit Lake drew many people in and was an important location in the political planning of the Odawa, as well as sharing of traditional knowledge. The LTBB Odawa gathered huge amounts of research, evidence and resources to present their case for reaffirmation. But in reality, this fight to have their treaty rights recognized goes back to the original treaty of 1836. Finally, in 1994, the LTBB Odawa status as a federally recognized Indian tribe in the United States was reaffirmed. The Odawa and their relationship to the water, again, played a major role in their history, with the connection to treaty rights for fishing and having those rights play a role in LTBB’s quest for federal status.

Beyond the politics, economy and the fact many Odawa lived right on the Great Lakes themselves, there is a very vital cultural component of water in the history and way of life for the Odawa. Numerous spirits dwell within the water and the Odawa interacted with them accordingly. The dead being interred near the water is only one element of the cultural connection. Many others have remained in modern Odawa communities. But much of this information is deemed culturally sensitive and transmitting it to groups outside of the Odawa community is often not permitted.

The fact remains that ceremonial interaction with water still occurs within Odawa communities. Such ceremonies differ from individual to individual. Some have been lost through time and others have been retained. The Odawa have weathered an intense barrage of assimilation in the last two hundred years. Under these circumstances, where it was American policy to eradicate native traditions, knowledge was lost. But what has survived is often guarded and passed down in the traditional manner.

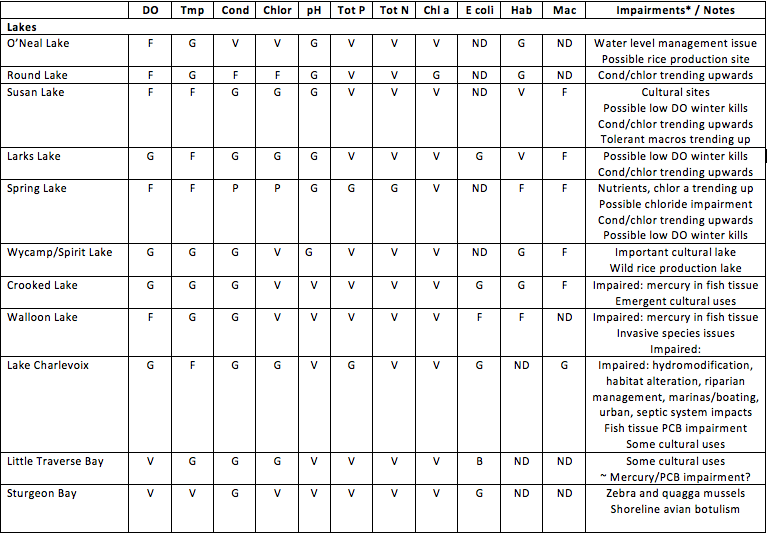

Table 3 provides a listing of monitored lakes, rivers, streams, and creeks in the LTBB reservation, a water quality data summary, and notes on impairments. Note that presentation of the water quality monitoring data in a summarized format does not include the more detailed analyses and information that are presented in the text. Water quality in monitored lakes ranged from impaired to excellent (Table 3). The most significant issues are fish tissue concentrations of mercury and PCBs and temperature in some of the shallower lakes. Elevated conductivity in some lakes may be linked to disturbance of natural marl substrates by boat motors and other activity.

Water quality in rivers and streams was found to be generally good to excellent, with scattered impairments. Water quality on tribal lands is affected by hydromodification and habitat alteration (i.e., alteration of channels and riparian areas), nonpoint source pollution (i.e., polluted runoff) from roadways and other developed areas, temperature, and fish tissue concentrations of mercury and PCBs. Tribal staff have documented that roadway stream crossings and channel modifications, in the form of culverts, bridges, or dredging, are causing erosion, obstructing fish passage, and resulting in warm temperatures and elevated nutrient concentrations at some locations. Channel modification and high temperatures affect river and stream fisheries because fish cannot find spawning and hiding places in streams with thick deposits of sediment, nor can they survive and reproduce above threshold temperatures.

A total of 152 river and stream impairments on and adjacent to tribal lands were noted, with approximately half resulting from alteration of channels and riparian areas. Stormwater runoff from urban areas is the second leading cause of impairment, followed by transportation infrastructure (including road maintenance), atmospheric deposition, agriculture/aquaculture, and marinas/boating (Table 3). The Crooked River watershed, which flows toward Lake Huron, has the most impairments, with 33 impaired reaches.

Table 3. LTBB monitored waters, with parameters summarized as poor (P), fair (F), good (G), very good (V), or no data (ND).

RICKY COMPO

TAMARA KIOGIMA

LEROY SHOMIN

DOUG EMERY

WILLIAM ORTIZ

MARCI REYES

KENNETH DEWEY

AARON OTTO

SHARON SIERZPUTOWSKI

SIERRA BODA (WITHDREW 5-14-21)

BERNADECE (BERNIE) BODA & LINDA GOKEE

REGINA GASCO-BENTLEY & STELLA KAY

(Click Team To Read Their Statements)

BERNADECE (BERNIE) BODA & LINDA GOKEE

REGINA GASCO-BENTLEY & STELLA KAY

(Click Candidate Name To View Their Statement)

Search Code Index

function search(string){ window.find(string); }

LTBB Events

Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat

Contact SPRING

[ninja_form id=12]

https://app.hellosign.com/s/LJki90VA