08 Mar Tribal Chairperson’s Statement Regarding Reservation Litigation

Tribal Chairperson Regina Gasco-Bentley has released a statement regarding the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa’s reservation litigation.

On Monday, February 28, 2022 the Supreme Court of the United States denied review of our case in Federal Court in which we sought affirmation of the reservation boundaries in the 1855 Treaty of Detroit. In legalese, the U.S. Supreme court ordered that “The petition for a writ of certiorari is denied.” We sought review of the May 28, 2021 ruling of the Federal Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in which the Court held that the 1855 Treaty did not establish a jurisdictional reservation. The Supreme Court’s refusal to review that decision leaves the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in place as final and binding.

This case cannot change the fact that this region has always been and remains our home.

Most important, this case in no way impairs the Indian Country status of our trust lands, our programs, services, inter-governmental agreements, or programs and services.

All of the following remain in full force and effect:

- Our off-reservation hunting, fishing and gathering rights throughout the territory that the Odawa and Chippewa gave to the United States in the 1836 Treaty, which stretches roughly from Grand Rapids to Alpena to Escanaba;

- Our jurisdiction over our Federal trust lands, which includes 47 parcels totaling about 1000 acres;

- Our Tax Agreement with the State of Michigan;

- Our right to exercise original jurisdiction over our children who live on our trust lands, and to transfer child-in-need-of-care cases to Tribal Court from State Court under the Indian Child Welfare Act and Michigan Indian Family Preservation Act;

- Our cross-deputization and mutual aid agreements, and fire protection agreements with counties, townships and municipalities.

- All of our federal, state and foundation grants.

- Our rights to operate our casinos under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and LTBB law.

So, this unfortunate outcome in federal court on our 1855 Treaty reservation boundary will not keep us from preserving our sovereignty, promoting our culture and economy, and providing services to our citizens.

Of course, we would have preferred to have won the case to honor our history and increase services to our citizens, and protection of our children, elders, lands and waters. The Federal Court affirming the reservation would have put the whole world on notice that the entire area reserved for us in the 1855 Treaty is our permanent reservation home. Even without the Indian Child Welfare Act or Michigan Indian Family Preservation Act, we would have had exclusive jurisdiction over our children throughout the entire reservation area. We would have had greater authority to protect the remains of our ancestors throughout the entire area under the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act. We would have had authority to protect Tribal victims of domestic violence and jurisdiction over Tribal citizens in the criminal justice system throughout the entire reservation area. These are the types of considerations that led the Tribe to take on this long, arduous and costly fight.

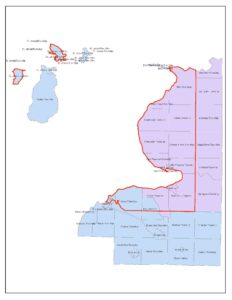

The area shown in the map was set aside for our ancestors in the 1855 Treaty of Detroit. The treaty expressly refers to this area as a reservation. Land within the reservation was to be allotted in parcels of 80 acres to families and 40 acres to single persons. Had the Treaty been properly implemented almost all the land within the reservation would have consisted of Odawa allotments. Mismanagement and fraud in the decades following the 1855 Treaty led to the loss of Odawa title, but the Tribe maintained that the jurisdictional boundaries of the reservation remain intact, just as a city or state’s boundaries contain land within them that are not owned by the government.

The 1994 Reaffirmation Act (Public Law 103-324) that reaffirmed the federally recognized status of LTBB and the Little River Band referenced the 1855 reservation, and LTBB’s Constitution that the citizenship adopted in 2005 and the Bureau of Indian Affairs certified, specifically defines LTBB’s reservation as the areas set aside for it in the 1855 Treaty. Dr. James McClurken’s historic research and publication of Gah-Baeh-Jhagwah-Buk during the late 1980s and early 1900s were critical in convincing Congress to pass the Reaffirmation Act. In 1996 the Tribe retained Dr. McClurken to research and prepare a history of LTBB’s reservation. Dr. McClurken spent years unearthing vast documentation in federal and Tribal archives that culminated in a 1000 page report which cited 5000 primary documents supporting the intent of the Tribal and Federal negotiators to establish a reservation in the 1855 Treaty that remains to this day. Over 17 years, from the mid-90s through 2014, the Tribe repeatedly requested that the Department of Interior issue an official opinion regarding the establishment and continued existence of the reservation. Tribal leaders and representatives repeatedly travelled to Washington to press the reservation issue and submitted legal memoranda to accompany the historic reports. The Interior field solicitor’s office in Minneapolis was favorably impressed with the McClurken report and we believe agreed with the legal analysis regarding the Tribe’s reservation. However, by the end of 2014 the Department of Interior did not take any official action to recognize the 1855 Treaty reservation.

The refusal of the State and local governments to recognize the 1855 Treaty boundary created a difficult situation for the Tribe and its citizens, especially in areas of child protection, criminal and domestic violence jurisdiction, and application of the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act. The situation put the Tribe and its citizens, who are bound by the LTBB Constitution’s definition of reservation, at odds with the State, local and even federal governments who refused to recognize the 1855 Treaty reservation. By the end of the 2014 the Tribal Council decided it needed to take decisive action to affirm the reservation, rather than letting the issue languish for future generations to grapple with.

The Saginaw Chippewa Tribe litigated a similar case 10 years earlier that resulted in settlement with the State that recognized their reservation through a series of agreements. The Tribal Council decided to retain the same legal team that represented the Saginaw Chippewa, who by then were in the Hogen Adams law firm out of Minneapolis, to assess litigating the LTBB reservation. Tribal Council ultimately authorized filing a law suit against the State of Michigan seeking a declaration that the 1855 Treaty established the reservation that remains in place and constitutes Indian Country.

In August of 2015 LTBB filed suit in the Federal Court for the Western District of Michigan against the State of Michigan seeking a ruling that the 1855 Treaty established a permanent reservation that continues to exist to this day. All of the local governments within the reservation, and two non-governmental entities, joined the case on the State’s side as co-defendants: City of Petoskey, City of Harbor Springs, Emmet County, Charlevoix County, Bear Creek Twp, Bliss Twp, Center Twp, Cross Village Twp, Friendship Twp, Little Traverse Twp, Pleasantview Twp, Readmond Twp, Resort Twp, West Traverse Twp, Emmet County Lake Shore Association, The Protection of Rights Alliance, City of Charlevoix, and Charlevoix Twp. Rather than litigating against a single defendant, LTBB had to litigate against 19 defendants. The two non-governmental defendants were particularly well funded.

Recognition of LTBB’s reservation area would designate it as “Indian country” which would allow the Tribe to more fully exercise its sovereignty and protect its citizens, natural resources, environment and ancestral remains, along with its cultural identity and the history of its members. Recognition of the reservation boundaries would reduce conflicts between the Tribe, State and local governments concerning competing claims of jurisdiction within the reservation. The only lands that the State and local governments currently agreed were “Indian country” were the parcels that are held in trust for LTBB by the United States.

Massive trial preparation took place between from 2015-2019, including all parties retaining numerous PhD historians, many discovery requests and depositions, and numerous pre-trial motions. In litigation plaintiffs or defendants may file motions for summary judgment claiming that there are no facts in dispute that must be resolved by a trial, and that they are entitled to judgment as a matter of law based on undisputed facts. In 2019, the defendants filed a motion for summary judgment asking the judge to rule that the 1855 Treaty did not establish a reservation. In August of 2019, without conducting a trial, the Federal District Court granted the defendants’ motion for summary judgment ruling that the 1855 Treaty did not establish a reservation, but only temporarily withdrew land from sale to allot to individual Odawa families. After amassing vast historical documentation, and the oral history of the Tribe, the summary judgment ruling denied the Tribe a trial in which to tell its story.

The Tribe then retained the Ann Arbor and Seattle based firm of Kanji & Katzen to lead the appeal because of their vast experience in Indian law appellate work including their recent successful representation of the Creek Tribe in the United State Supreme Court in a case that affirmed a large portion of the State of Oklahoma as the Creek reservation. The Tribe filed its appeal of the August, 2019 ruling with the Federal Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. On May 18, 2021 a three judge panel of the Appellate Court issued its opinion upholding the District Court’s August, 2019 ruling. We were heartbroken by that decision which fundamentally misconstrued our history. We then requested rehearing before all of the 16 judges of the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, but the Appellate Court denied that request.

Our last avenue was to seek review in the United States Supreme Court. On the advice of Kanji & Katzen, we had Ian Gershengorn of the Washington DC firm of Jenner & Block lead the Supreme Court effort. Mr. Gershengorn also worked on the McGirt case representing Mr. McGirt, is frequently retained by NCAI, and served as acting Solicitor General in the Obama administration where he was largely credited with preserving the Affordable Care Act. The Supreme Court only grants cert. (accepts a case for review) for about 2% of the petitions. Based on the critical historic and jurisdictional issues raised in our case, and the Court of Appeals opinion’s contradiction of United States Supreme Court and Appellate Court precedent, we made a strong case to come within that 2%. Sadly, the Supreme Court turned down our petition to review the Court of Appeals decision.

After so many years of work by Odawa citizens, staff, historians and attorneys, at a cost of about $8.5 million dollars for the years of trial preparation and historic research, and about $670,400 on the appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court’s denial of cert ended our case without even an opportunity to present our testimony at trial. This is profoundly disappointing and frustrating, but only strengthens the resolve of the Odawa to continue building our culture and community in this land of our ancestors.

A full version of the statement will also be included in the next Odawa Trails issue.